https://mondoweiss.net/2020/10/the-enduring-power-of-rachel-corrie/

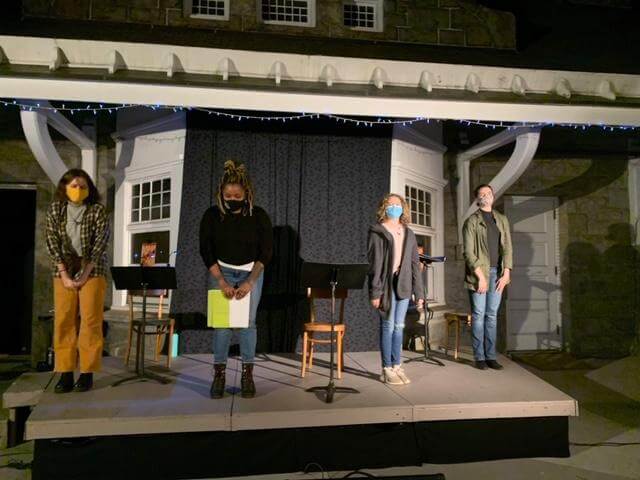

Two Saturdays ago, a theater company near me presented a reading of the play, “My Name Is Rachel Corrie,” with four young women speaking Rachel’s words on a simple stage 50 feet from commuter rails.

About 60 people were in the audience, and there was none of the political drama that accompanied the play’s New York premiere in 2006. Israel’s friends did not succeed in shutting down a progressive theater company‘s production of the show… When the show did get staged, no one handed out flyers outside the theater.with pictures of Israeli girls killed in suicide bombings

Yet in a way the play had more raw power last Saturday night than it did when I first saw it 14 years ago. Director Christine Bokhour chose the work because she was looking for a piece that would tie into Black Lives Matter and other protests. “[Rachel Corrie’s] passion for social activism, and willingness to put her own life on the line for it, is what is inspiring to me,” Bokhour wrote in the program. “I cannot imagine a time when I would have had the courage to do what she did.”

For anyone who doesn’t know: Corrie was an Olympia, WA, writer who died at 23 in 2003 in Rafah, Gaza, as a volunteer for the International Solidarity Movement, when an Israeli bulldozer crushed her as she was trying to protect a Palestinian home from demolition.

Her words are familiar to me. Her published journals, letters and poems helped propel me into this work in the first place. I can see her book on my shelf as I am working now: “Let Me Stand Alone“.

But Rachel Corrie’s words were new to my wife and two friends in the audience that night. And at the end of the show they all sat quietly with their eyes on the ground. My friends were both too upset to talk that night, so I caught up with them later.

Each said the play’s power lay in the fact that we get to reimagine the conflict through an young American’s idealistic eyes.

“It resonated in a small town way,” said Sheila Rauch. “The seriousness of what she was doing came through because of the four small town girls on the stage. I thought, Rachel Corrie could have been just like them. No, not every person is as socially conscious as Rachel Corrie was. But all those girls were relating to her.”

Rauch went on, “All the things you have heard before about this conflict — they were in the play, but through the eyes of someone so young, so unprotected, and so American, whose whole understanding is American. When she said, I’m so pathetic, how can I be the best hope for these people who are being so hospitable to me — I was overwhelmed by the tragedy of it.”

My second friend, Celia Barbour, also said she was familiar with Israeli army demolitions, but overcome by hearing about them in a young woman’s sometimes awkward voice.

“The early portions of her diary are almost wincingly personal in places, like when she’s in middle school and high school,” Barbour said. “But the silly parts just make her story more devastating at the end. It makes her more human, which is the real strength of the piece.

“The way she grappled with her privilege also had huge impact on me. A lot of us have been thinking about these issues lately. The choices we make to support our comfort and safety, they don’t feel like political acts. But just maintaining your own comfort and safety can have enormous political implications.”

And Palestinian hospitality also touched Barbour.

“I was moved by her description of the hospitality of her Palestinian hosts, especially the fact that they wouldn’t accept money from her, their generosity of spirit and simple kindness. Because we seldom experience that kind of open-heartedness here in America, we are so defended and protected against one another. We don’t welcome strangers into our houses, share our homes and tables with them. Here in the US it seems that the more you have, the more you close your doors.”

The tensions between the child’s innocence and the activist’s worldly awareness gave the play its power to Barbour.

“What you see in the late correspondence with her parents is that she becomes so articulate in her understanding of the politics. The assurance in her voice in those pleas to her parents– we’ve all been in that position; we were once that kid engaged in that discussion, finding our voice and strength, standing up for what we believe. And it adds more emotion to the piece. Her parents argue from what they’ve heard in the news: there are terrorists on both sides. But by this point she has grown to have not just an emotional and personal engagement, but an intellectual engagement that makes her voice so much stronger. You’re feeling the entire complexity of a person engaging in a struggle. And all the pieces come together in a wallop. That is quite beautiful.”

Corrie herself was angered that her white Westernness protected her, and the fact that it doesn’t in the end of course helped put the story in headlines around the world. And led in time to this play (Corrie’s words edited by Alan Rickman and Katharine Viner) and to streets in Palestine being named after Rachel Corrie.

I can’t help tearing up whenever I think of Rachel Corrie. I imagine what she would have done with a longer life. But it is clear that she made the most of what time she had… and her words will echo for a long time in our country.

No comments:

Post a Comment